|

A Brief History of Radio Spectrum Management IN CANADA From the Early 1970’s leading up to Computer Automation in the early 1980’s

Maurice R. Drew - February 2006

Several years before decentralization of frequency assignment and licensing operations to the regions of Canada in the early 1970’s all frequency assignments and licensing was conducted by the Department of Communications at the Radio Regulations Branch at Ottawa Headquarters. They were interesting times because radio technology was rapidly outstripping the ability of the few at Headquarters, including myself, to keep up with the demand for commercial, interference-free radio operations. New frequency bands were becoming available and commercial mobile radio was rapidly migrating from the unreliable and inefficient low bands to VHF and UHF.

When I went into the Radio Reg's Branch in 1974 part of my job was to select, assign and authorize frequencies to all non-broadcasting radio services in Canada. My job also included assigning frequencies, from the shared land mobile bands, to the Department of National Defence. Computer automation was almost ten years into the future. It was an amazing place with perhaps seventy or eighty clerks all on one floor who typed radio station licences and transcribed information from copies of application forms to other types of paper forms. The typewriter noise was deafening and the air thick with smoke from cigarettes, cigars and pipes.

The people who headed up the Branch were the Director, W.W. Scott, a likable and more than competent man who wore pin striped suits with a gold chain attached to a watch in his vest pocket. He was a man of dignity, smoked cigars on occasion and made young newcomers feel comfortable in his presence. Al Heavenor, a quiet spoken but no-nonsense man headed up the Frequency Assignment and Licensing Division. Al could not tolerate incompetence so if you didn’t measure up you moved out on your own accord. There were no awards, just satisfaction of doing the best that one could in the circumstances.

This is a brief look into the past and tells a story of events that made a difference in the development of a discipline by a few people who were doggedly determined to pull it off. There may be inaccuracies and omissions. This is almost inevitable in such a complex history. There are numerous individuals who could be looked upon as movers and shakers and are extra special. You know who you are. But as in any lengthy missive my objective, due to limited resources and memory, is not to be absolute and thorough but to highlight certain influences, in spite of barriers, along the way.

As this story will reveal spectrum management in Canada from the early 1970’s to the mid 1980’s was crude and low-tech. It was learning and developing from mistakes that made us the best radio regulatory administration in the world.

There have been a few old timers and some younger-timers who helped in telling this important history. Some of the names will be familiar, others remain a distant memory. Just the same, they all did their part and have earned their place in history. I have highlighted some names throughout the text which indicates their involvement in various programs.

Special thanks go to Bob Jones, currently in retirement and enjoying being closer to his family. Apart from being Director General of the Branch in Ottawa for many years, Bob was elected to direct the Radiocommunication Bureau of the International Telecommunication Union in Geneva, Switzerland; and to Tom Racine, Ottawa, Ontario, in retirement, sort of, who has been and continues to be an incredible mover and shaker throughout his career. Tom is omni-competent and can be described fondly throughout his involvement in the branch as a one-man-band; to Art Solomon, also in retirement, who remembers his contribution to spectrum management with pride. Art lives in Guelph, Ontario; Bob Bissell, currently the Director of the Kelowna District Office, who grew up on puréed spectrum management in the Ontario Region. Bob has been instrumental in remembering better – but he’s much younger than most of us; Vic Decloux has been an inspiration and a valuable source of ideas and specifics. Vic was once called the father of spectrum management. To him I say, thanks, dad; and to Kevin Paterson, currently the Executive Director, SITT in Winnipeg, for positive feedback; then there is Laval Desbiens, who put me up to this in the first place. Laval has been feeding me ideas on important issues, fanned the flames and has supplied photos and lots and lots of good memories. For additional information on contributors to the development of spectrum management in Canada check the biography section of the spectrum website: http://www.spectralumni.ca/index3_e.htm

Spectrum management was our livelihood, of course, and we wanted to do a good job. But, more than anything else, we wanted to do it our way, the right way.

Early Databases

Before computer automation there were many different types of databases used at Headquarters and in the regions of Canada. All of them were paper-based, single-user systems that proved inefficient and subject to instant destruction. And even after computers were widely available to staff in the department in the early 1980’s there could not be effective technical analysis of any kind because our databases were not complete, amalgamated or accurate.

The Radio Station Licence Database

When an applicant applied for a radio station licence it was required that four copies of an application be produced. One copy of the application was kept by the Licensing office at Headquarters, one copy went to the applicable region and one to the district responsible for enforcing the regulations applicable to the licensed station. The original, I presume, was retained by the applicant.

Until decentralization original applications were kept on file at Headquarters in a central registry that took up half a floor of a high rise building and employed at least fifteen administrative staff together with a mountain of material resources and a budget to match the demand. Each regional and district office also maintained an essential file registry ultimately duplicating files maintained at Headquarters.

If an application described a complex microwave network it was much more convoluted and cumbersome than a typical land mobile radio system because there were engineering briefs required which consisted of maps, drawings, engineering studies and support correspondence that often made a file several inches thick. These kinds of files were maintained in a separate location at Headquarters that piled up to become a hazard for anyone needing a file from the bottom of the stack.

When a licence was issued there were five copies produced which were distributed similarly to that of the application form. One copy of every radio station licence in Canada was kept on file at Headquarters by the Licensing Division. There were thousands of copies, each stored in regional order and by radio service. The licences were produced in different colors for each type of radio station and there was a licence issued for virtually every radio station requiring a licence, including all mobile stations. Copies of invoices were similarly maintained. Imagine the paper burden on some licensees such as large metropolitan taxi companies!

There was a great deal of pride in being able to keep track of tons of paper and justifying one’s existence in the scheme of things. However, no matter how efficient the administration might have been and the effort that went into it the paper database was never complete. Not by a long shot. The reason was that well into the 1980’s the Department of Communications did not licence federal government radio stations nor did they pay a fee. And municipal administrations were issued only one base station licence and one mobile station licence regardless of how many existed within the municipality and no matter how many frequencies were listed on the licence. So in the case of Montreal, Toronto, Winnipeg and Vancouver, for example, hundreds of base and mobile stations and associated frequency assignments were never properly registered! Furthermore, in keeping with the one-licence policy municipal clients paid for only one base and one mobile station. The licence fee for many years was seven dollars and fifty cents! At the time there were economic reasons for this policy. Looking back in retrospect, particularly in the computer age, it was pretty sloppy.

The Frequency Assignment Database

The frequency assignment database (exclusive of licences) at Headquarters up to the early seventies was a huge library of black, three ring binders. The database was, of course, single-user and available only to those who resided within easy access. And only one person could access one volume and one page at a time. The database listed all frequencies up to the VHF band, 138-174 MHz. Microwave assignments were also registered as they were licensed. The 400 and 800 MHz bands had not become available for general assignment until the early to mid 1970’s. By this time the black binders had become somewhat obsolete.

Each page listed a single frequency with all company names who had been assigned that frequency. All relative information was printed in a single line or perhaps two if using the space could be justified. More often than not a place name such as Ottawa and an address and telephone number was all that located the assignment! Geographical coordinates were used mostly when an assignment was in a remote area.

All Canadian assignment entries were in black ink and when an assignment had been cancelled a thin red line was drawn through it so that potentially important information would not be obliterated. Green ink was used to describe an assignment in the United States that might have potential to conflict with a Canadian assignment. Commentary such as licensing infractions and reports of harmful interference was entered in red ink.

Occasionally, there would be two or three blank pages indicating that the frequencies were not assignable. In these circumstances, there would be a brief note on each page with a reference to “the pouch” which represented the so-called “secret” list of assignments. The pouch was available to only a handful of staff with a security clearance of secret.

There was little or no usable technical information in the frequency assignment database. Needless to say, due mostly to lack of engineering skill and lack of essential information, technical analysis by radio regulators of the time was not practicable.

To my knowledge none of the old binders have survived years of progress. This is unfortunate because many of the entries were made with an old straight pen with a steel nib that was dipped into a bottle of ink. Back in those days people took pride in penmanship and many of the entries were scribed with an attractive flare. How priorities have changed!

The Headquarters Cardex System

A similar procedure to the black, three-ringed binders was applied in maintaining records of frequency assignments coordinated with the United States. The coordination information was recorded on two by four inch lined cards and kept in stacks and stacks of drawers. The cards were manually updated by our Division clerk Louis Guindon and there was no provision in our many disconnected agreements with the United States for informing us when a station might be decommissioned. Therefore, removing entries was not possible and decisions could be made only on a by guess and by golly basis. One card, or many taped together to form a single continuous record, represented a single frequency assignment. The cards grew and grew… On more than one occasion I recall the drawers being knocked over and the contents spilled onto the floor. It took hours to stick them back together and hopefully in their correct order in the drawers. In time the so-called Cardex System would become untenable.

Although some regional and district offices in Canada at the time had begun to maintain more accurate records than ever before there is one office that stands out among them all. The Montreal office had a huge topographical map of the Quebec region. The map was supported by a wooden frame and had become a sophisticated and impressive looking plethora of colorful pins, tags and strings. Each pin represented the exact location and frequency assigned to every station in the area. It was knocked over one evening by cleaning staff which resulted in instant database destruction. The crash was heard from coast to coast and I’m sure there were tears shed over the crisis.

Early VHF (138-154 MHz) and the Frequency Selection Process

The VHF band available for commercial radio in the late fifties to early seventies was 138-154 MC/s (later MHz). The standard bandwidth was 30 kHz and occasionally 36 kHz! As technology improved and became available the bandwidth decreased to 16 kHz. There was no frequency plan for the band and for the most part operational policy was willy-nilly. To some extent, it’s still that way! All of these kinds of assignments resided together in the same radio environment! The radio service allocation for the band was fixed and mobile, except aeronautical mobile. It was with seemingly gleeful ignorance that no discrimination was made between the land mobile and fixed services when assigning a channel within the band regardless of location and potential conflict!

Standard procedure for selecting a frequency for land mobile and radio paging operations was somewhat random as long as the correct band was used and we knew the band limitations of a client’s radio equipment. Once a potential frequency was selected the approximate location of the station was plotted on a 1:50000 scale topographical map. A three inch piece of string was tied to a large straight pin. The pin was placed at the station location on the map and the other end of the string was used to scribe a circle on the map. If the proposed frequency was not already assigned anywhere within the circle it was assignable! This procedure was applied to both single frequency (simplex) as well as two frequency (duplex) operations. If one or the other frequency could not be made to be compatible using this procedure another frequency was selected without much consideration for frequency separation or channeling policy. It was up to the radio equipment supplier to make it work, usually at considerable cost to the client.

As technology and knowledge improved so did frequency and spectrum policy. Channelling plans were developed that made sense from an engineering perspective. Actually, when the 400 MHz band opened, due to technology development, Canada had most of the channels assigned before the FCC in the United States could get their rules together and published. This was about 1974 or so. This meant that most of the band along the US/Canada border was not mutually available to the public in the United States. This crisis was averted by simple genius - or another one of those, take-a-bow scenarios. With the distances between the border and the spectrum separation all we needed to do is split the channels so that the US got the half channels and Canada got the whole channels. For those of you who know what I’m talking about, both the US and Canada got the same amount of spectrum without causing mutual interference. That’s the theory, and it averted an international crisis. To those involved, well done!

Channel Occupancy Measurements

In the early days of VHF and UHF development there was no practical means of determining to what extent a channel was actually used or occupied at any given time. Therefore, the policy of the time dictated an assumption that two base stations and fifty mobile stations was the maximum loading for each channel assigned in the same radio environment.

It wasn’t until the spectrum surveillance (SSS) program was developed and made into a practical operation by staff at the Acton Spectrum Services Center in Ontario and in St. Rémis, south of Montréal, that channel occupancy wasn’t anywhere near what we had assumed. By the late 1970’s we could determine with reasonable accuracy to what extent the sharable spectrum was available.

Tom Racine wrote most of the original software for the SSS and has memories of how the Spectrum Surveillance System was developed and the early days of spectrum scanning conducted from various places. He writes:

For a bit more in the early development of the SSS go to the web address http://www.spectralumni.ca/z_1975_better_service_planned.htm. It’s amazing to see how the early monitoring program has evolved into a network of remote sensors described as Integrated Spectrum Occupancy Centers (ISOC) that covers southern Ontario and Quebec. Eventually the program will include all of the most populated areas of Canada.

Art Solomon also has specific memories of how the Ontario Region responded to channel occupancy requirements in the Golden Horseshoe back in the early 70’s and 80’s:

Once the Spectrum Surveillance System was developed and considered operational it was transferred to me in operations. I had been following the advances, believed in them, and had met with those directly involved. Following some rather dicey meetings with regional and Headquarters staff we met at the Acton Spectrum Services Centre to determine how to proceed. Nearly a year later, and many sessions with staff from the Québec and Ontario regions at a hotel in Kingston, Ontario, we had a functional transportable system assembled that met objectives within a manageable budget.

Software interface between scanning receivers, broadband antennas, and computer equipment was developed by the equipment supplier. But the monitoring data display, in living colour, was developed by Elie Chahine together with Headquarters and regional staff. We could actually watch on a video monitor as radio signal information for either discrete channels or groups of channels was being transmitted in real time!

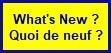

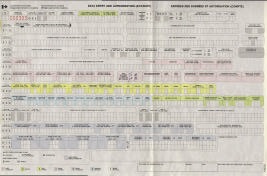

The illustrations above are examples of how actual occupancy information was produced. The scale at the bottom of the upper picture indicates the 24 hour period over which a channel was scanned. The numbers at the top of the report indicates the percentage of occupancy over each hour scanned. The red bar is the highest occupancy at that hour and the yellow bar indicates the mean value for the thirteen hours the channel was scanned. Many different types of reports were produced in the early 80’s and except for more sophistication today the information produced remains pretty much the same. As can be appreciated, the old policy of two bases and fifty mobiles is no longer applicable.

While the channel occupancy and system analysis data collected remain much the same today as it was earlier on, the reporting system and the hardware systems used to collect the data have been improved on an on-going basis to meet changing spectrum management needs and the requirements of Industry Canada District, Regional and Headquarters spectrum managers.

Some years later, Glen Ritchie, the manager of the Acton, Ontario Spectrum Services Center, would demonstrate that they could track radio signals from the flight path of an aircraft approaching Toronto International Airport on a digital map displayed on a computer screen. This means that any radio signal, whatever the source, as long as it was within range of our sensors, could be tracked and located.

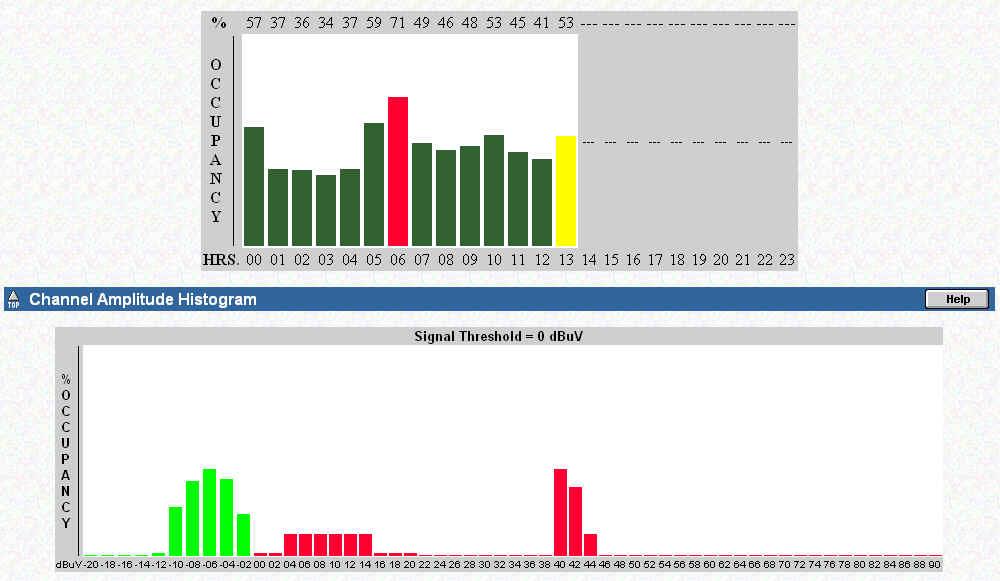

Early Radio Coverage Confirmation and EMC Analysis

In the early 1970’s Hewlett Packard produced the first scientific calculators suitable for completing engineering studies. Before scientific calculators were developed slide rules were used, if any kind of analysis was completed at all. Although some affordable computers were gradually making their way into the business world it was scientific calculators such as the HP65 complete with magnetic recording strips that stored programs that could be re-loaded into temporary memory that got the ball rolling for many of us. These developments encouraged a more scientific approach to authorization. I believe that I was the first at Headquarters to apply a scientific approach to authorization by directing the DND to reduce the power of a base station from 120 to ten watts, then asked the Halifax office to follow up to ensure that the reduction had been affected.

After the HP65 came the more advanced HP67 and ultimately the HP41 series with alpha-numeric display and advanced programmable characteristics. Other relics applied in the early days can be viewed at the spectrum alumni website system_photos.htm

Around the mid 1970’s the Central Region in Canada, under Howard Smith in Winnipeg, developed a program for confirming radio coverage and applying the system in their authorization process. The program was called EMCANAL and was maintained originally on computer facilities at our CRC laboratories at Shirley Bay near Ottawa.

EMCANAL was used extensively in the Central Region prior to development of the official Assignment and Licensing System (ALS) by Headquarters. The Central region was well on their way to developing a full-blown automated EMC analysis system but by this time the Radio Branch at Headquarters under Bud Hoodspith began the early stages of developing computer automation with a view to a national standard. Consequently the Central region could not obtain funding for their database development at the University of Manitoba.

And from Laval Desbiens we get:

Radio Wave Propagation Models

Propagation models developed under John Egli combined with a location variability loss model developed by Anita Longley were the most commonly applied in determining radio coverage parameters for land mobile applications. The Central region applied a combination of models including fade margin, shadow loss and Bullington nomograms for confirming operational parameters for the fixed radio service operating in the VHF/UHF bands.

Although the Ontario region began using a more sophisticated and complex model for land mobile radio coverage determination, largely developed by Tony Fodero and Jack Gavigan, they eventually conformed to the simpler Egli standard.

The Free Space propagation model was applied in land mobile, EMC analysis and included co-channel, adjacent and interstitial frequency analysis, transmitter and receiver intermodulation analysis and desensitization analysis. Microwave EMC analysis also included the Free Space model together with many other complex criteria that applies exclusively to the fixed and space radio communication services. The microwave sub-system wasn’t put into operation until several years after national expansion in 1980/81.

A few interesting anecdotes came out of this era. One is where a large telecommunication company in Manitoba constructed a high radio tower near Portage La Prairie which supported a 180 watt (ERP) transmission. The objective was to provide radio paging signals to the surrounding territories of Winnipeg and parts east and west. After many angry disputes with the regulators in Winnipeg and many long hours of negotiation the telecommunication company was instructed by Howard Smith supported by his regional executive under Irwin Williams to reduce their power to one watt based on both theoretical calculations and field strength measurements.

Another involved the famous CN Tower in Toronto. Many of the first radio paging and dispatch systems at the tower were to be high powered. After Vic Decloux and many of his staff were finished with the engineering companies the power was usually authorized with much less than requested.

Bob Bissell remembers how it was at the Toronto office when the CN Tower was under construction:

We had suddenly become more sophisticated, a lot more confident in our abilities and began to realize that unless we also became more prudent in collecting and accurately maintaining complete databases we could never rely on our engineering applications.

We were young and ambitious and no problem was too big to be solved so we set out to fix the database.

Progressive Database Development

In 1974 Tom Racine appeared on the scene and began work in the newly formed engineering Division. It was Tom who developed a computer program he called DFLM. The program and associated data files resided on computers at our CRC laboratory at Shirley Bay. Information used by the program came from massaged data from the DFL files presumably stored on magnetic tape. DFLM was a deceptively simple list of frequencies together with associated technical data that I could call up on a dumb terminal at my office and produce a customized list of frequencies and data that I could use in the frequency selection process. It was a marvelous development that cut my workload dramatically. It was a taste of the future but it was short lived. Tom could not get funding to continue essential updates. However, while it was in production I used it to apply a crude means of EMC analysis. For the first time, in Ottawa at least, I could deny an assignment based on actual engineering predictions. As can be imagined, however, I had trouble convincing my bosses of this new approach and was directed on more than one occasion to approve an assignment, as submitted. When interference eventually occurred, as I had predicted it would, I was given more autonomy.

Some government offices in the early seventies had begun essential records keeping to newly developed microfilm. Later on microfilm and the costly associated reading machines would be replaced with microfiche. The Radio Branch took advantage of this new technology and began to store frequency assignment and licensing information on film. One has to understand the bureaucracy of the time and that the licensing and frequency assignment operations were conducted by separate Divisions. So naturally each Division was responsible for only their records maintenance. What came out of this was that the Integrated Radio Licensing System (IRLS) and the Domestic Frequency List (DFL), separate licensing and frequency assignment databases, containing duplicate fields of information were maintained on separate film, updated under different schedules by different people using different forms and published separately under different schedules.

Tom Racine remembers it well:

Consequently, neither of the DFL and IRLS databases was ever in harmony with the other, due partially to the separation of a two week publication schedule. Therefore, a licence record described in the IRLS often contained different technical and administrative information from its associated DFL frequency assignment record! For those of us involved in the frequency selection process it was terribly frustrating.

Warp Speed Into the Future

In 1975 a team of scientists, engineering staff, mathematicians and regulators were assembled in Ottawa. Their objective was to plan for the development and implementation of a computer-based Spectrum Management System (SMS). Throughout the development process the program was called the SMS. The SMS was to be a national standard and would, ostensibly, replace all existing programs, models and databases. An early prototype is described in http://www.spectralumni.ca/z_1979_sms.htm. We can look back in smug satisfaction because it worked. The same cannot be said for similar initiatives undertaken by the CBC, CMHC and other high profile government departments at the time. A few notes from one of the Departments newsletters sum it up:

Before we congratulate ourselves, however, we must look back at reality. Although regional and Headquarters staff were good at managing the radio spectrum a lot of it was personal knowledge and there were a lot of “persons” in the department. Few of the regulators knew anything at all about computers and those who knew computers didn’t know spectrum management. To flush out the intelligence we had national conferences and working groups whose job it was to formulate agreements on how to compile methods, process, database structure and a whole lot more. It took years. To say that some of the meetings were acrimonious is a polite alternative use of four letter words. They were interesting times but I wouldn’t change a millisecond even though I came out of it with a few bruises.

The SMS took five years and more than seven million dollars to develop. Following live trials in Winnipeg and Montreal the newly tagged Assignment and Licensing System (ALS) went into production in December 1980 on a region-by-region basis. The Atlantic region was smaller than the other regions and was considered a reasonable test bed for the others to follow. Quebec went on line in January 1981 followed by Ontario, Central and finally the Pacific region signed on in July of 1981.

The fur flew for months afterwards because many of the staff throughout the country had become habitually comfortable in their established methods and didn’t want to change. When Bud Hoodspith set up the budget for automated SMS development he should perhaps have made cash available for a few psychiatrists. One has to remember that hardly anyone knew what a computer was in those days. The best that could be said about many is that they could at least spell it in their formal complaints.

Milestones and Growing Pains

It wasn’t enough that we had a fully operational and national system – we needed a complete and accurate database. Some of our assignment records dated to the 1930’s and no one could say if these remote operations were still valid. On the other hand, any new records were authenticated before making it into the database. This was great but we couldn’t wait years before incomplete and inaccurate existing records were displaced. What to do…

The Department hired hundreds of young college students. Whoever thought this one up, take a bow. The students were given a crash course on how to do a preliminary inspection of a radio station. They were then set loose into designated areas with forms, special instruments and initiative to compile the requisite information. The task took nearly two years but it did the trick. Once the information was uploaded into the computer files our data became much more useable. However, this wasn’t nearly enough…

At around the time of final SMS development certain policies were being formulated that would see the end of exempting federal government and municipal radio administrations. New policy, and some existing regulatory direction, were enacted or enforced. No one would be exempt from licensing. What’s more, they would pay! Imagine the reaction from the DND, RCMP, municipalities and many others. The program was not only successful from a policy perspective but two major events took place that changed our way of doing business forever.

Suddenly, because administrations had to pay for every frequency and licence hundreds, if not thousands, of channels became available for reassignment as no longer being required. The other benefit was that since all administrations were no longer exempt from licensing all new and existing frequency assignments had to be properly and accurately registered. Bob Jones remembers it well:

It took two or three years but the database finally took shape. It may not be perfect, even to this day, but it’s close enough to get the job done with professional integrity.

The DFL and IRLS reports continued to be published for a short time after the ALS went into operation but quickly ran out of favour with the regions. The US administrations, with which we exchanged frequency assignment information, were also frustrated with the inconsistent approach taken by our reporting system. Although a new national reporting system was under development to replace the IRLS and DFL it was found to be too large, cumbersome and costly to put into production. Until computers became more powerful with almost unlimited memory capacity, and were much cheaper, there was, and still is, a need for a national reporting system.

Technical and Administrative Frequency List (TAFL)

The need for a comprehensive reporting system spawned the development of the Technical and Administrative Frequency List (TAFL). I did the original planning and layout in collaboration with all of the regions. It didn’t take long before I got full agreement to proceed. Charles Chang did the coding and the first TAFL went into production initially as a paper document. Thousands and thousands of pages were printed at CRC and shipped to the regions and districts in hundreds of boxes.

Since TAFL was an ad-hoc initiative there was no budget for its development or processing. Therefore, part of the agreement between the development group and operations was that the regions had to pay for processing time on a per capita bases. This was worked out by determining the number of frequency assignment records in each region and dividing this number into the total cost of the database extract. If memory serves, the Atlantic paid the least at about $68 and Ontario paid the most at $210 every time the report was produced. The report was updated four times a year. Eventually it was produced on microfiche then made available in digital format. This means that anyone today who has access the department website can obtain frequency assignment data, except for secure information. It’s still in production twenty eight years later!

Another milestone (c1981) that resulted from automation is that the Central Registry at Headquarters was no longer necessary. Any information that was required was accessible, on a multi-user basis, directly on-line to anyone in the country. Therefore, the entire records management system in Ottawa was dismantled and the staff re-assigned. This initiative alone saved hundreds of thousands of dollars annually.

Updating the New ALS Database

At the beginning of automation the method of database updates had changed dramatically. New forms were designed to ensure that all elements of information were correctly formatted for upload. There were two data entry forms, the 16-888 represented licence information including company name, addresses and other administrative data essential for licence production. The other form was the 16-889 and was designed for frequency data. There would be only one 16-888 form but there could be many 16-889 forms depending on the number of frequencies assigned to a specific station.

The forms were colourful, convoluted and were an anomaly in an automated process. The forms had to be completed then shipped to a processing center where the information was key-stroked onto magnetic data tape then uploaded to the computing facilities two days later.

Subsequent to the key-stroking operation, maintenance reports were produced and shipped to the regions and Headquarters for review. Errors had to be corrected using yet other paper forms and submitted for update that took another day or two. It was not efficient.

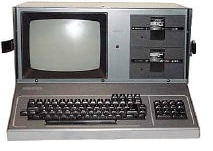

However, at this stage of development Tom Racine had been free of much of his responsibilities as a principle in-house guru. He set out to develop what was known as the On-Line Data Entry System (OLDE). Before long the paper forms had taken on digital format and resided on a portable computer called the KAYPRO-4. Data was entered into the computer then saved to a floppy disk (they were actually quite thin and floppy). The floppy data was then downloaded to the so-called mainframe and the records updated the same evening. Maintenance reports were produced at the end of the update and shipped the next day to the respective offices and Headquarters. The catch was that the regional transmissions were made through the facility of risky, somewhat primitive, telecommunication lines.

There was another predictable issue that needed to be addressed. At one of our national conferences we discussed whether there should be a double entry requirement for some of the more critical data elements. Three of the more obvious are frequency, latitude and longitude. If an error was made at the data entry level of any of these components it is not likely that the error would be immediately noticed. The consequences of such errors could adversely affect the integrity of EMC analysis and other applications. In as much as the need for double entry was stressed by some the regions would not hear of it citing a waste of time and they didn’t want a machine baby sitting the staff. To this day when an environment check is completed for larger parts of the country several hundred frequency assignment records are situated (by data entry error) in the Pacific Ocean, Lake Ontario and the Atlantic Ocean. These are easily confirmed as errors. It would take considerable effort to determine accuracy of all other entries.

( The Environment Search is a program that will produce custom specified records based on location, frequency and many other components. For example, by specifying a frequency assignment within a certain geographical radius, that frequency together will specified components will be produced either on paper, computer screen or digital map. )

Although the On Line Data Entry System significantly reduced the need for paper, the Québec region didn’t like the way the initial OLDE program had been assembled because it would not facilitate some of their localized, stand-alone programs. This prompted the Ontario and Central regions to demand the same. Suddenly, it was necessary to maintain four separate update systems at the mainframe and our standard approach began to crumble. As will be seen in the next few pages, several of the stand-alone programs developed by the regions were incorporated into the main frame.

The Operating System

I remember the controversy over what operating system should be used to manage our database. Like many others at the time I listened with interest but didn’t understand a word of it! ORACL was an operating system that supported a relational database structure but it was new. The other system under consideration was System Two Thousand (S2K) which supported a hierarchical database structure and was developed out of Texas in the United States. We decided on S2K and, to some extent, our database structure is based on this system to this day even though S2K hasn’t been supported for years!

Database Control and Maintenance

In the early days of national expansion the Department had budgeted for day-to-day costs of all computer transactions. There were no stand-alone servers in those days and computer hardware was very expensive and computer memory quite limited. Therefore, contracts were set up where we used computers and associated communication facilities owned by a service bureau. Our first service bureau was Canada Systems Group (CSG). Access to the service bureau was achieved through dumb terminals and communications links that were slow by today’s standards. The more users on the system, the slower it got. So slow, in fact, that it wasn’t unusual for staff to become impatient while waiting for their data links to connect or disconnect. The “escape” key was often used to terminate such transactions. The problem with striking the “escape” key was that although it appeared as though a transaction had ended the transaction user identification would remain connected to the service bureau running up the bills! When a user who had terminated a transaction in this fashion and wanted to get back in they had to call the operations office in Ottawa who, in turn, had to call the service bureau to get them logged off so that the user could log back on!

Another peculiarity with the arrangements of the time was that all transactions at the service bureau were monitored and registered by the service bureau using service bureau facilities. At the end of each day the service bureau would produce a transaction record and ship it to Headquarters for review and approval. When the transaction record was approved the service bureau would send an invoice. Eventually, the auditors caught up with this activity and ordered an independent examination.

Some of our more remote offices did not have access to efficient communication services. I remember trying to appease staff from Whitehorse who attempted to transmit their daily updates through a 300 baud telecommunication link through no fewer than four telephone companies! There were not that many records but it took hours and broke their budget in no time.

Eventually, a Facilities Management Contract had been arranged between the department and the service bureau. The contract was for a five year period, renewable annually, and it cost about eight million dollars! It was costly but it meant that all users in the department could use the system without cost over-runs and budget calamities. Over the years, there have been many progressive changes in both the method of doing business facilitated by rapid advances in computer and telecommunication technology.

Before long many staff in the regions became not only computer literate but became programmers themselves. This resulted in many programs being developed that were impressive. For example, the Québec region developed an engineering program for processing complex antenna farm data. They also developed an electronic filter program and many others. One of the more notable is GDOC. GDOC is a radio licence application tracking, document management, and process workflow tool that is still in use across the Country today. Other useful tools were also developed by Quebec and other Regions. Dennis Lanthier notes it this way:

Accolades by the Auditor General

On a final note, the Auditor General of Canada typically finds many ways to scold the government for waste and inefficiency. However, the Radio Branch of the Department of Communications was justifiably proud to read his remarks in the 1988 and other Audit Reports to Parliament which is quoted here, in part, by Liz Edwards:

Auditor General praises Spectrum Management

Kenneth M. Dye, F.C.A. Auditor General of Canada Ottawa, 8 September 1988

By Liz Edwards

Conclusion

As I write this story, February 2006, the entire automated SMS is being reviewed for redevelopment under what is known as the SIRR project at the Radio and Broadcasting Branch of Industry Canada. Although computer technology has advanced incredibly since the beginning of the SMS there remains the human factor to deal with. It won’t be easy and I’m glad I’m not there.

|

|||||

|

Links - Liens

|

|||||